July 4th History

This page includes a brief summary of the events that led up to the American Revolutionary War and the subsequent independence that we celebrate on July 4th. I hope this history will give you and your family a deeper appreciation of the sacrifices that were made for the birth of our nation and government — so that we can preserve it. For, in the words of William Jennings Bryan, U.S. Secretary of State, “Our government, conceived in freedom and purchased with blood, can be preserved only by constant vigilance” (1908).

Please note that the below history is available as a FREE July 4th History eBook (which includes the text of the Declaration of Independence).

Introduction

The holiday we know as July 4th, or Independence Day, celebrates the day on which America declared itself independent of British rule. So what were the events that led up to the Declaration of Independence?

The conflict between American colonies and their mother country, Britain, had been brewing for a long time. In the early 1600’s, newly established American colonies were barely surviving. But with time, they began to prosper, and by 1660, the British established the first of their Navigation Acts.

The Navigation Acts decreed that certain American products (like tobacco, cotton, and sugar) could only be shipped and sold to England. Furthermore, all goods bound for the American colonies had to be shipped first to England. To make matters worse, the British government also limited the colonies from manufacturing certain goods (clothing, furniture and machinery), demanding instead that they import these items from Britain.

Though these acts frustrated colonists, there were mixed opinions about them. On one hand, colonists had a guaranteed market for their goods, as well as a powerful partner to negotiate with foreign sources for their import needs. On the other hand, colonists were aggravated by their dependence on Britain. Regardless, true animosity did not really seem to build until Britain began imposing taxes on the colonies.

Boston Massacre

Beginning in 1764, British Parliament passed a series of taxes that were extremely unpopular in the colonies. The Sugar Act of 1764 and the Stamp Act of 1765 were viewed by colonists as stifling to an already struggling economy. Then came the Townshend Acts of 1767, which introduced new taxes (designed by British Chancellor Charles Townshend) to cover the cost of salaries for colonial governors and judges. Though American dollars would be the source of funding for these salaries, Britain would hold the “purse strings” (ensuring that these colonial leaders remained loyal to Britain). Americans were further angered by the fact that they had no representation in British Parliament. Thus the mantra of the colonists became: “No taxation without representation!”

The Townshend Acts were so unpopular in America that Britain had to send troops to the colonies in 1768 to enforce them. Americans deeply resented the British occupation (which was headquartered in Boston), and anger exploded into violence on March 5, 1770. A riotous crowd of colonists threw snowballs, rocks and other small objects at British soldiers inciting gun shots that left five Boston men dead and many others wounded. News of the incident spread quickly through the colonies, and it later came to be known as the “Boston Massacre.”

Ironically, on the same day as the Massacre, British Parliament had voted to remove taxes on everything but tea. There was an uneasy peace for about three years, until the British passed the Tea Act of 1773.

Boston Tea Party

The Tea Act of 1773 was designed to help the financially struggling British East India Company. It did not impose any new taxes on colonists, and it would actually decrease the cost of British tea in the colonies by allowing the East India Company to sell directly to America. Originally the company had been required to export their tea exclusively to Britain, where they would pay taxes and then sell to merchants. These merchants would then ship the tea to America and pay the required Townshend tax. This process resulted in very expensive tea for Americans, and the British assumed that sales would increase if they could reduce the cost of tea.

But what many in the British Parliament failed to acknowledge was that Americans were not as bothered with the expense of British tea as with the Townshend tax that was attached to it. They opposed the tax because of their strongly held view that there should be “no taxation without representation.” Under the Tea Act of 1773, the Townshend tax remained in place even though some in Parliament warned that it would probably provoke another colonial controversy.

The other major problem with the Tea Act was that many American merchants had established successful businesses by smuggling Dutch tea to the colonies. Keep in mind that smuggling was considered a legitimate business by most colonists. Even though many Americans preferred British tea, they encouraged one another to buy Dutch tea as a protest of the Townshend tax. The Tea Act was seen as an attempt to undercut the cost of Dutch tea and put American merchants out of business.

Before sending tea to the colonies under the new Tea Act, the British East India Company contracted with consignees in America. These consignees would get a commission for selling tea in the colonies. As soon as American protesters learned about the plan, they went to work convincing consignees to either resign their positions or return the tea to England. They were successful in every colony except Massachusetts where Governor Hutchinson refused to return the British tea and convinced the consignees, two of whom were his sons, not to back down.

When protestors realized that Hutchison was not willing to budge, a group of some 30 to 130 men (reports vary) boarded three ships sitting in the Boston harbor, and with some disguised as Mohawk Indians, they dumped all 342 chests of tea into the water. The date was December 16, 1773.

When word of the “Boston Tea Party” reached Britain, Parliament was outraged and responded by establishing what are known as the “Coercive Acts.” They closed the port of Boston until the East India Company was repaid for the tea; they changed the government of Massachusetts by allowing the governor or king to appoint almost all positions in the colonial government; and they allowed the governor of Massachusetts to move trials of accused royal officials to another colony or even to Great Britain if he believed the official could not get a fair trial in Massachusetts.

The intended purpose of these acts was to make an example of Massachusetts and reverse the trend of colonial resistance to parliamentary authority. But the acts had the opposite effect. Many Americans became even more hostile toward Britain and feared that their colonies, like Massachusetts, might be Britain’s next target.

First Continental Congress

Tension remained high, and by September 1774, delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies traveled to Philadelphia to attend the First Continental Congress. The delegates agreed they needed to take action against Britain, so they established a boycott of British goods. They also published a list of rights and grievances and petitioned King George to repeal the “Coercive Acts.” They agreed that if Britain was unresponsive to their petition, they would reconvene for a Second Continental Congress.

Meanwhile, Britain was sending more and more soldiers and weapons to deal with rebellion in the colonies. In response, Americans organized groups of volunteers that they called “Minutemen” (men who were ready to do military service at a minute’s notice).

American Revolution Begins, The Battles of Lexington and Concord

In April 1775, British General Gage learned that Americans were storing military supplies at Concord, and he sent British soldiers to seize them. They were also instructed to arrest Patriot leaders John Hancock and Samuel Adams.

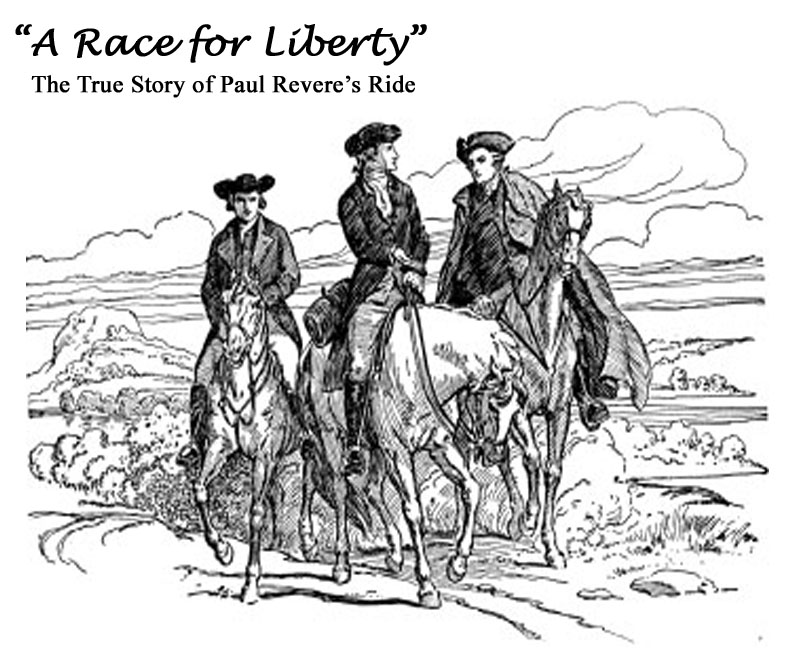

On learning of the movement of the British soldiers, Paul Revere and William Dawes began their famous Midnight Ride to Concord. They alerted Minutemen along the way that the British were coming, and they arrived in Lexington in time to warn Hancock and Adams. When the British arrived in Lexington on the rode to Concord, they met with the resistance of a small group of Minutemen who fired muskets. Many Minutemen were killed or wounded, and they retreated as the British marched on to Concord.

Meanwhile Samuel Prescott joined Revere and Dawes on their journey to Concord. Contrary to the popular belief that Revere successfully arrived in Concord (based on Longfellow’s poem “Paul Revere’s Ride“), Revere was actually caught and detained. Dawes fell off his horse and was not able to complete the trip, but Prescott arrived in Concord in time to alert the people.

Minutemen gathered in large numbers at a small bridge in Concord, and when the British arrived, a fierce battle ensued. The British soldiers were forced to retreat to Boston. In the end, 273 British soldiers and 94 Minutemen (18 of them in Lexington) died.

The battles at Lexington and Concord marked the first armed clashes between British troops and Americans, and they are considered the first battles of the American Revolution. The poet Ralph Waldo Emerson coined the phrase “the shot heard ‘round the world’” in his Concord Hymn (1836) to emphasize the significance of these battles in world events.

Second Continental Congress (and the Battle of Bunker Hill)

A month later, in May 1775, the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia. Recognizing the need for a united military, they named George Washington commander-in-chief of the American armed forces. But they knew that the colonies were by no means ready for all out war, so they determined to attempt a peaceful settlement with Britain. They prepared a message for King George, known as the Olive Branch Petition, explaining that though the colonies remained loyal, they had many complaints against Parliament. They begged the king to cease further military action so that both sides could have time to negotiate a peaceful agreement.

The following month, while the Petition was en route to Britain, another significant battle, the Battle of Bunker Hill, took place. On June 13, 1775 colonial forces learned that British generals were preparing to send troops out from Boston to occupy the surrounding hills. In response to this intelligence, 1200 colonial troops, under the command of William Prescott (uncle of Samuel Prescott), set out to position themselves at Bunker Hill and the adjacent Breed’s Hill. They built a fort system and fortified their lines.

When the British learned of the presence of the colonial troops, they mounted an attack on June 17, 1775. After repelling two assaults, the colonial army ran out of ammunition. On the third assault, the British were able to capture the hills, but not without significant casualties. Over 800 were wounded and 226 were killed, including a notably large number of officers. Meanwhile, the colonial forces were able to retreat and regroup having suffered few casualties.

Before the Olive Branch Petition reached King George, he received news of the Battle at Bunker Hill. He was furious, and in response, he issued “A Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition” on August 23, 1775. The Proclamation declared that the colonies were in a state of “open and avowed rebellion.” It ordered British officials “to use their utmost endeavours to withstand and suppress such rebellion” and encouraged British subjects to report anyone who carried on “traitorous correspondence” with the rebels so that they could be punished.

In September 1775, the Second Continental Congress received the king’s Proclamation. They also learned that the king was unwilling to receive their Olive Branch Petition. Some members of Congress were ready to declare independence immediately, but other leaders wanted to allow the king more time to change his attitude toward the colonies.

Unfortunately, time proved that tensions between Britain and America were only increasing. In March of 1776, George Washington and his Continental Army successfully forced the British to evacuate Boston. In response, Parliament ordered British merchants to stop all trade with the colonies and commanded the British navy to seize American ships at sea. Though these actions were intended to break the rebellious spirit of the colonies, they only served to strengthen America’s resolve to break ties with Britain.

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia stood in Congress and proposed the following resolution for independence:

“That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”

The motion was seconded by John Adams. But it soon became clear that five colonies were not ready to make such a dramatic declaration; more importantly, they had not been authorized by the people of their states to make such a decision. The vote was thus delayed for three weeks, so that these congressmen could have time to determine the will of their people. Meanwhile, a congressional committee would work on drafting a formal declaration. The committee was made up of five men: Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingston and Roger Sherman.

Because Thomas Jefferson was known to be a superb writer, the committee asked him to prepare the first draft. As John Adams would later say, “If George Washington was the sword of the Revolution, Thomas Jefferson was the pen.”

The Declaration of Independence

For the next several days, Jefferson labored to produce a declaration. In a letter to a friend, John Adams recalls the next events:

“It was read (to the committee of five), and I do not remember that Franklin or Sherman criticized anything. We were all in haste. Congress was impatient, and the instrument was reported, as I believe, in Jefferson’s handwriting, as he first drew it.”

On June 28, 1776, the committee submitted its draft of the Declaration to Congress. But the first order of business was to vote on Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence. An initial vote taken on July 1, 1776 showed nine of the thirteen colonies now in favor of the resolution. Delegates from Delaware and New York disagreed among themselves, so these colonies abstained. Pennsylvania and South Carolina both voted “no,” but South Carolina said that if Pennsylvania and Delaware voted for the resolution, they would cast a vote in favor of it as well.

Supporters of independence quickly went to work in an effort to persuade their opponents to reconsider. They knew that they needed the support of all of the colonies if they were going to war with Britain. On Tuesday, July 2, when the final vote was taken, two of Pennsylvania’s seven delegates (who were opposed to the declaration) stayed home resulting in a final vote of 3 in favor, 2 opposed. Pennsylvania’s vote was cast for independence.

Next came the dramatic entrance of Caesar Rodney, one of Delaware’s three delegates and a strong supporter of independence. Rodney had missed the initial vote because he was suffering from cancer. But a messenger traveled 80 miles to explain the situation and the urgent need for his vote. Rodney left at daybreak and rushed to reach the State House in time. He arrived in a state of complete exhaustion, but asked to speak as soon as possible. He said, “As I believe the voice of all sensible and honest men is in favor of independence, and my own judgment concurs with them, I vote for independence!” So Delaware’s vote was cast for independence, and South Carolina followed as they had promised to do. Lee’s resolution passed twelve to zero, with only New York abstaining.

In a letter to his wife Abigail, John Adams wrote of that day:

“The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires and illuminations, from one end of the continent to the other, from this time forward forever.”

But before any celebrations took place, Congress still had critical work to do. They had to approve the document that would explain their decision to the world. For the next two days, the delegates worked tirelessly to agree on the wording of the Declaration of Independence. According to John Adam, “Congress cut off about a quarter of it, as I expected they would; but they obliterated some of the best of it.” Sadly, part of the portion that was cut from the final draft was the condemnation of the practice of slavery. The final text was adopted on July 4, 1776. It was this day, not July 2 (as Adams predicted), that would be celebrated every year thereafter.

It should be noted that the Declaration was not signed by all the delegates on that day. Only John Hancock, president of the Congress, who is most famous for the first and largest signature on the final draft of the Declaration, and Charles Thomson, the secretary of the Congress signed the original draft.

On July 15th Congress received word that the Provincial Congress of New York voted to approve the Declaration, so on July 19th, Congress resolved:

“That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment with the title and stile of ‘THE UNANIMOUS DECLARATION OF THE THIRTEEN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA’ and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress.”

This specially prepared copy of the Declaration was signed on August 2nd by most of the delegates, with the remaining members signing later. “Some delegates, including Robert R. Livingston of New York, a member of the drafting committee, never signed the Declaration” (www.ourdocuments.gov). This is the copy that can be seen today at the National Archives in Washington D.C.

It should also be noted that no celebrations took place in Philadelphia on the first July 4th. It was not until four days later, on July 8th, that the Declaration was read aloud at noon in the yard behind the State House. Colonel John Nixon, commander of the city guard, was chosen for his powerful voice. He began with the now famous words:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

Colonel Nixon went on to read through the unjust acts of King George and Parliament toward the colonies and how the colonies had pleaded for peaceful negotiations to no avail. He concluded with the powerful words:

“That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, free and independent states; that they are absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political Connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved.”

See the full text of the Declaration of Independence.

There was great rejoicing in Philadelphia that day. According to John Adams, the bells of Philadelphia rang all day and through most of the night.

As copies of the Declaration were distributed to every community in America, the people celebrated with cheering, parades, and bonfires (generally burning anything connected with British rule). And though American soldiers had scarcely enough gunpowder for their weapons, they fired their guns and cannons throughout the land.

News soon reached George Washington in New York where he and his troops were stationed for an expected British attack. Washington ordered that the Declaration be read to the troops on July 9th with the following words from him:

“The general hopes this important event will serve as fresh incentive to every officer and soldier to act with fidelity and courage, as knowing now that the peace and safety of his country depends, under God, solely on the success of our arms, and that he is now in the service of a state possessed of sufficient power to reward his merit and advance him to the highest honors of a free country.”

These words could not have come at a better time for increasing the morale of the American troops who would soon have to face British General William Howe and his 10,000 troops (soon reinforced to 32,000) who had landed on Staten Island on July 2.

Furthermore, the troops were assured that they were not the only ones putting their lives on the line; so was their Congress whose closing statement of the Declaration said:

“And for the support of this Declaration, with the firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor.”

The Revolutionary War

Sadly, the ecstasy of the first celebrations of Independence were short lived. Just one month later, in August 1776, Washington’s army was defeated by Howe’s troops at the Battle of Brooklyn. British troops then seized New York City and extended into New Jersey (Trenton and Princeton). But by late December 1776, Washington and his troops crossed the Delaware and gained back the New Jersey territory.

Though there were glimpses of hope over the next several years of war, it was an extremely challenging time. Washington’s army, mostly dressed in tattered clothes, suffered from cold and hunger. Many had neither uniform nor shoes. It hardly seemed that they could withstand their opponents – orderly British soldiers in fine red coats who seemed to show up in an endless line of reinforcements.

But Providence brought about a decided turn in the war when other European countries agreed to assist America in their war for independence. Though France had been covertly supplying arms and finances since the beginning of the war, they signed a Treaty of Alliance in 1778 that openly promised military support to America against their British opponents. The following year, in 1779, Spain became an ally to France, and in 1780, the Dutch became allies as well. This alliance provided strategic support to America by creating a powerful blockade in the Atlantic Ocean between Britain and America.

Then came the most significant event of the war. In 1781, British General Cornwallis surrendered after his army came under siege by a combined force of French and American armies in Yorktown. When the news reached Britain, political support for the war (which had already been waning) plummeted, and in 1782, Parliament voted to end the war. Preliminary peace articles were signed in November 1782, but the formal end of the war did not occur until the Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783.

The new young United States realized that it needed strong leadership to help it recover from war and establish itself as a strong and stable country. Not surprisingly, George Washington was elected as the first president of the United States in 1789. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, who were instrumental in drafting the Declaration, were the second and third presidents respectively. Interestingly, exactly fifty years after the Declaration was adopted, July 4, 1826, both Adams and Jefferson passed away. For many, this was a confirmation of God’s providential hand in history.

NOTE: There has been much debate in recent years regarding the Christian commitment of our Founding Fathers, as well as whether or not they intended to establish a “Christian nation.” You can learn more about this on our page: “Was America Established as a Christian Nation?”

This page was created by:

We welcome your ideas! If you have suggestions on how to improve this page, please contact us.

You may freely use this content if you cite the source and/or link back to this page.

Image Credits:

The Boston Massacre: Wikimedia Commons

The Boston Tea Party: Wikimedia Commons

First Continental Congress: Wikimedia Commons

Paul Revere Statue: Wikimedia Commons

Battle of Bunker Hill: Wikimedia Commons

Franklin, Adams, and Jefferson: Wikimedia Commons

Declaration Before Congress: Wikimedia Commons

Washington Crossing the Delaware: Wikimedia Commons